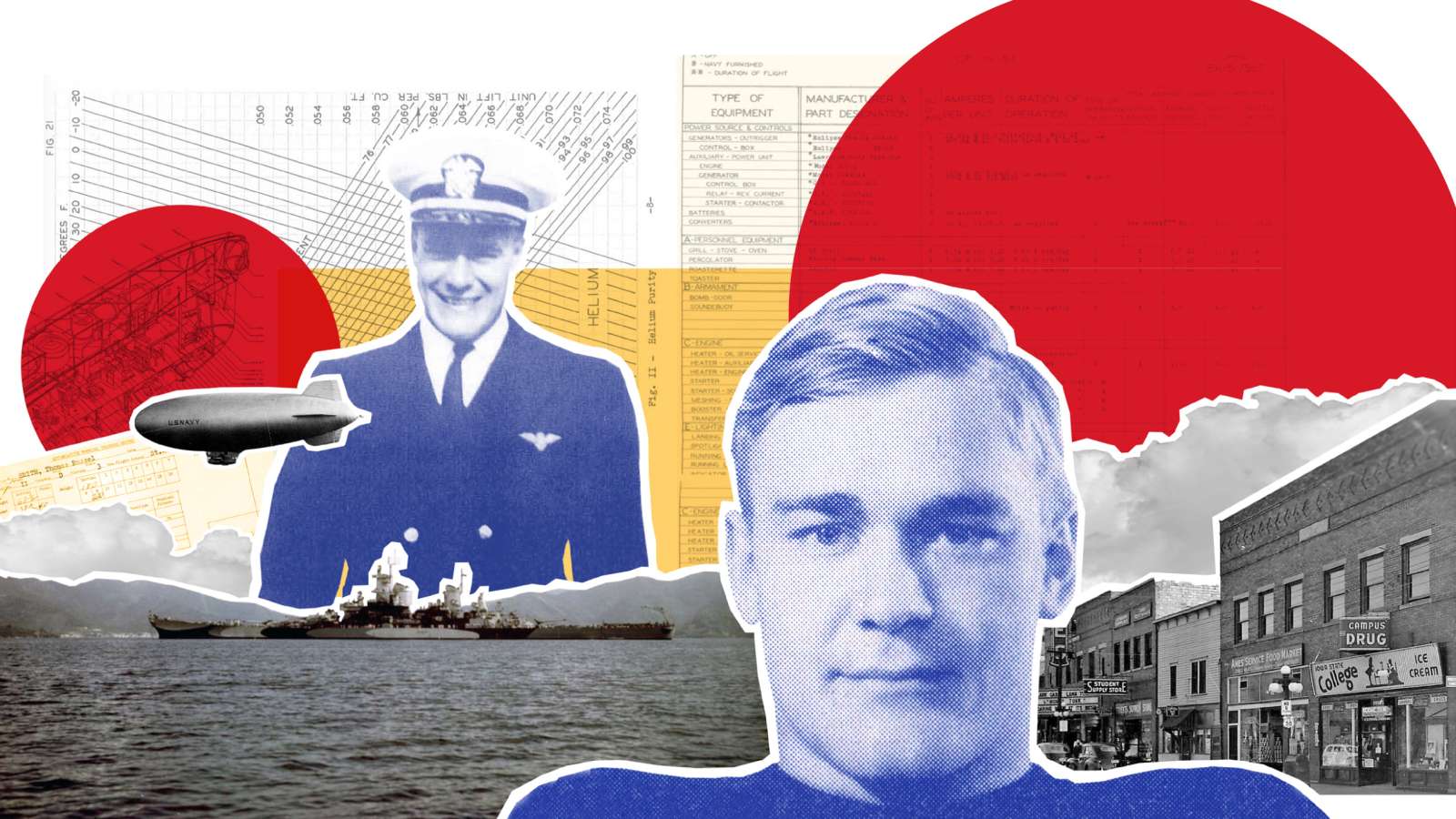

Thomas Smith (’68, ’71) never knew his namesake, Tom Russel Smith (’42).

While stories of his uncle were scarce, Thomas Smith had a link to his family’s and alma mater’s past. For years, in Thomas and his wife Evonne’s (’68) Texas home, there was a trunk containing a large wool cardinal blanket with gold etching containing the year 1941; his uncle’s fraternity, Kappa Sigma; and his uncle’s name.

The blanket, presented as recognition for Smith’s selection as Iowa State’s Athlete of the Year for the 1940-41 school year, included three letter stripes and a star, signifying his status as captain of the 1940 Cyclone football team.

“When President Wendy Wintersteen came to visit us, I took the blanket out of the trunk and we took a picture,” Thomas Smith says.

That image opened the door to a reexamination of his uncle’s life.

Tom Smith had an ordinary name. He lived a short but extraordinary life.

Smith was raised in Boone, Iowa, 17 miles west of the Iowa State campus where he would make his name. His father, Arthur Smith, ran a florist business in town.

Smith demonstrated his prep football toughness using spare telephone poles purchased by the Boone school board as tackling dummies.

Smith chose to attend Iowa State, where he was admitted to study horticulture. Smith eyed a roster spot on the Cyclone football team, but a place on it was anything but certain. Iowa State head coach “Smilin” Jim Yeager was skeptical that Smith would be able to withstand the demands of guard play in the trenches of the Big Six Conference. Players competed on both offense and defense and rarely came out of the game.

“When I first saw Tom, he was wearing an oversized pair of pants and a torn green sweater,” Yeager later said. “He was the most gosh awful looking freshman I’ve ever seen.”

Yeager gave Smith the toughest test he could imagine, pitting him in practice against the heart of the Iowa State line: All-American and College Football Hall of Fame guard Ed Bock and future NFL regular Clyde Shugart. They pushed Smith up and down the field. After several series, Smith, with a serious face chimed “any time you guys have had enough, just tell me and I’ll ease up on you.”

Smith passed the test. He was one of only 16 sophomores to earn a 1938 varsity roster spot.

With Bock and Shugart in the line, and ably led by nifty All-American halfback Everett “Rabbit” Kischer, the 1938 Cyclones far exceeded the expectations of nearly everyone.

For the next two years, Smith was at the core of Iowa State teams that went 2-7 in 1939 and 4-5 in 1940. During his senior season, Smith had called signals for the team, a rarity for an offensive lineman. Limited substitution rules meant Smith was often choosing what play would be run by the Cyclone offense.